Making it in America [REPORT]

July 1, 2017

![]() By James Manyika, Gary Pinkus, Sree Ramaswamy, Katy George, John Warner, and Andrea Serafino

By James Manyika, Gary Pinkus, Sree Ramaswamy, Katy George, John Warner, and Andrea Serafino

The United States needs to regain its competitive edge in manufacturing while also grappling with its two-tiered labor market and finding ways to make economic growth more inclusive.

The United States always assumed that its forward momentum would carry the next generation toward greater prosperity, just as it took for granted that its technical prowess in manufacturing would guarantee its global market share. But now those assumptions have been upended. Although unemployment is down and wages are finally ticking up again, these indicators can distract from the bigger picture. Tens of millions of workers are struggling to make it in America, and even a full-time job does not guarantee a decent standard of living.

Manufacturing is not the only sector with poor wage growth, nor is it the largest. But it was once the backbone of the middle class, and its erosion is symptomatic of broader shifts in the economy. Part 1 of this research preview looks at how this unfolded and outlines how the sector could exploit changes in technology and value chains to compete for new market opportunities. Part 2 traces what has happened to wages across the economy more broadly and considers what caused these pressures. Finally, Part 3 starts a conversation about solutions that can lead to more inclusive growth.

US manufacturing needs to regain its competitive edge and retool for the 21st century

Manufacturing remains a pillar of the US economy and the primary industry in some 500 counties, of some 3,000, from coast to coast. The sector drives 30 percent of the nation’s productivity growth, 60 percent of its exports, and 70 percent of private-sector R&D spending—all factors that keep the nation’s innovation machine humming.

But manufacturing now accounts for just 9 percent of US employment, a much smaller share than two decades ago. Excluding computers and pharmaceuticals, value added in most other manufacturing industries is no higher today than it was in 1997. The United States has lost market share not only to low-cost countries in labor-intensive industries but also to other advanced economies in knowledge-intensive industries. Today there are 30 percent fewer US manufacturing firms than in 1997, and the sector has lost roughly a third of its jobs. Not only have plants closed, but fewer are opening. The United States remains the world’s second-largest manufacturing nation, and the diversity of its industrial base presents multiple opportunities for growth. But the nation cannot afford to let its manufacturing muscle continue to atrophy.

Today demand, global value chains, and technology are evolving in ways that play to US strengths. The United States can capitalize on these shifts to boost output and narrow its trade deficit, particularly in advanced manufacturing industries.

- The first promising factor is rising consumption in emerging economies, combined with the fact that the United States itself remains one of the world’s largest and most lucrative markets.

- Factor costs are changing, too. Wages are rising in emerging economies, automation weakens the case for labor arbitrage, and the shale boom has made energy cheap and abundant in the United States. More of the world’s production is up for grabs; global value chains are shifting as firms emphasize service-based business models and proximity to markets, suppliers, and innovation partners.

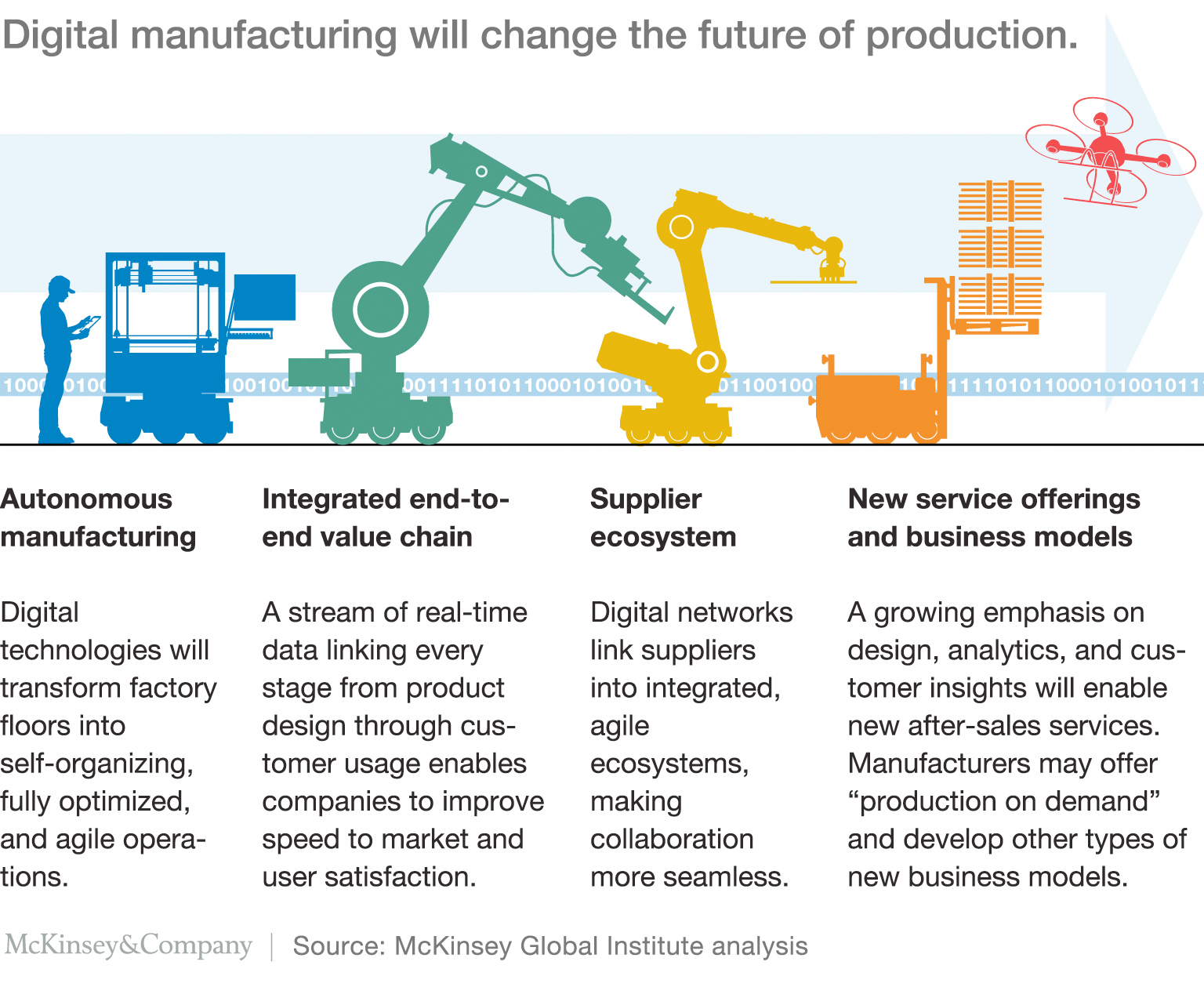

- The new world of digital manufacturing (Exhibit 1) represents a profound shift toward higher productivity and the agility needed to meet fragmenting demand. Technologies such as the Internet of Things, analytics, advanced robotics, and 3-D printing are transforming factory floors into flexible, self-maintaining operations. Companies will soon be able to connect their entire value chain with a seamless flow of data, unlocking efficiencies and new service offerings.

The growth opportunities for US manufacturing are real, but it would be naïve to minimize the challenges of turning around two decades of negative trends.

- This effort has to start with stimulating a wave of investment from both domestic and foreign sources—not just with tax incentives but through targeted strategies to bring the industries of the future to communities that have been left behind.

- The second critical priority is revitalizing the domestic supplier base, which has been hollowed out in the past two decades. Most US manufacturing firms are small companies that need financial, technology, and advisory support; large firms can take a step toward building their own collaborative supplier networks by helping smaller firms modernize and become more innovative.

- Third, the jobs at stake in 21st-century manufacturing may be service roles or positions requiring digital skills, which means that workforce training will be an important piece of the puzzle. Larger companies will have to do more to develop the capabilities they need by offering their own training, partnering with education providers and industry groups, or establishing workforce platforms.

- Finally, the United States needs a comprehensive strategy to boost net exports and regain global market share—one that encourages more small firms to participate, bringing the benefits of globalization to more workers.

US manufacturing can achieve a turnaround if the public and private sectors treat it as a national priority. But it is important to recognize that a successful revitalization will not produce a return to 1960s-style manufacturing employment. For decades the sector provided economic mobility to workers with less education, and nothing else has emerged to take its place. Part 2 of this report looks at the broader trend of narrowing opportunities.

The United States is increasingly a two-tiered economy, with millions of workers struggling to get by

Previously published MGI research found that 81 percent of US households were in segments that experienced flat or declining market incomes from 2005 to 2014. This reflects what a powerful blow the Great Recession delivered. But a longer view shows that pressures had been building for more than three decades.

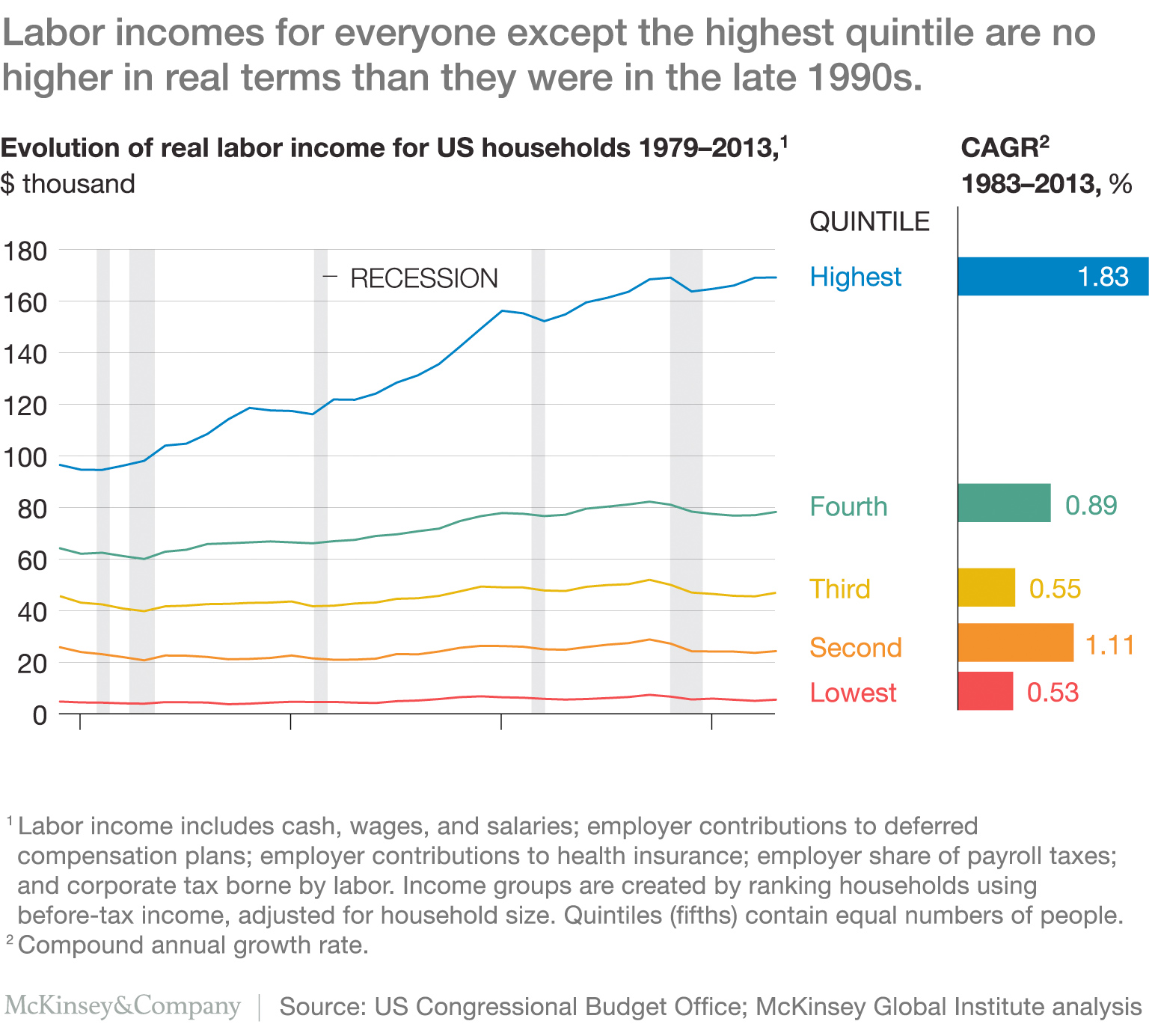

Declining household incomes are ultimately a wage story—and only workers at the top of the distribution have been bringing home bigger paychecks. The top quintile almost doubled its wages and benefits in real terms since 1983, but everyone else remains stuck at roughly the levels of the 1990s (Exhibit 2).

There is now a yawning pay gap between workers with postsecondary education and those without it. While a small number of high-growth metropolitan areas have bounced back strongly in the recovery, real median household incomes remain below their pre-2000 peaks in almost two-thirds of US counties. Meanwhile, the costs of maintaining a middle-class life have continued to climb.

Multiple economic, technological, and societal forces have simultaneously contributed to pressures on incomes and wages.

- Some are structural shifts, such as the changing sector mix of the economy and the declining share of national income going to labor. Productivity and wages have historically risen hand in hand, but now that relationship has been weakened. In the past two decades, the ongoing digitization of the economy has also made it possible to get more output from knowledge-intensive capital using less labor. There is a new premium on highly skilled workers who can make the most of technology.

- These long-term forces were exacerbated when the Great Recession struck. It caused a massive loss of economic output and was followed by a weak and highly uneven recovery.

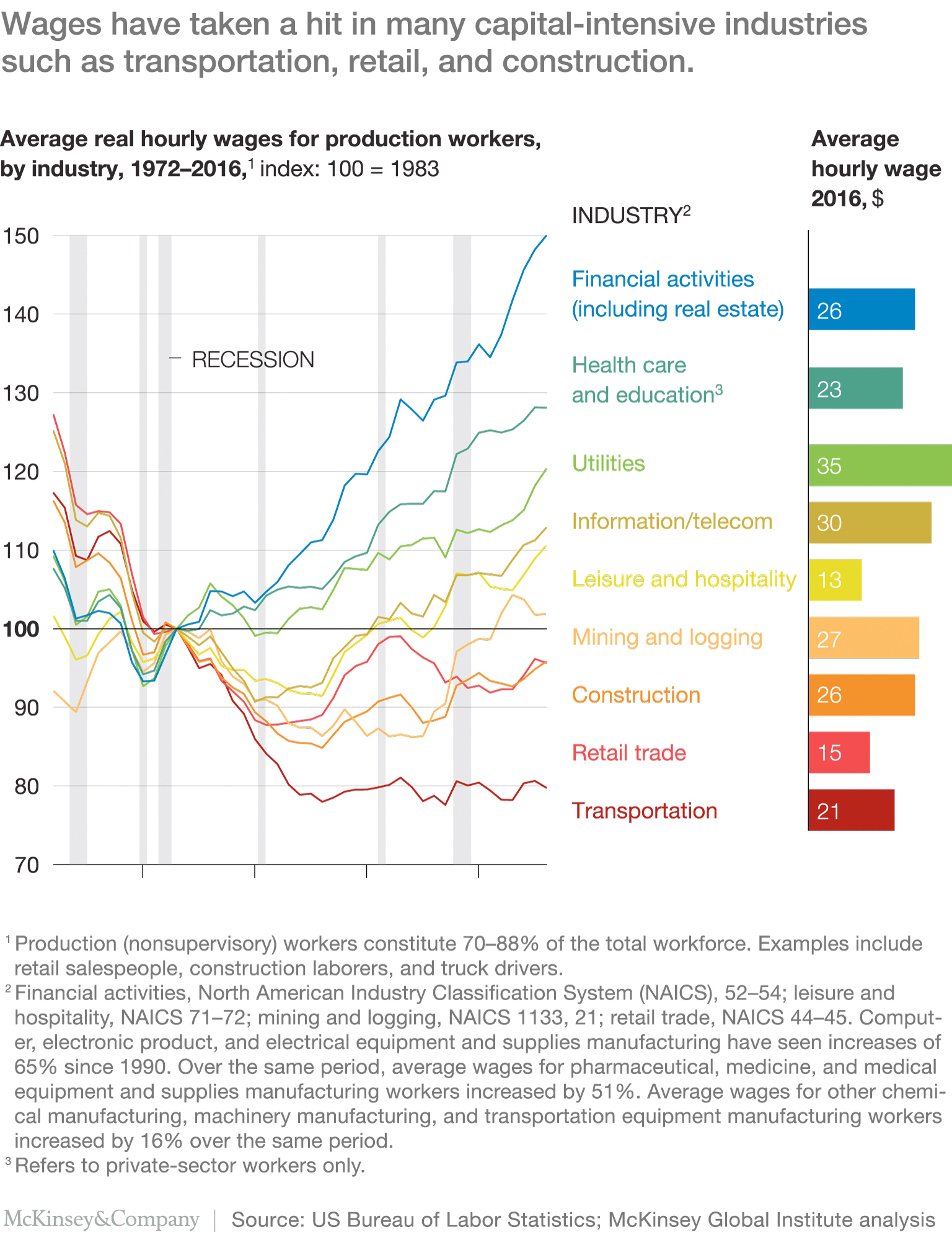

- All of the forces above have played a role in depressing wages. In addition, we highlight another potential contributing factor that is often overlooked in discussions of US income inequality: the changing environment facing companies and industries. There has been an extraordinary escalation of competitive pressures—including foreign competition in tradable sectors as well as price competition and declining returns in many asset-heavy sectors. Furthermore, profits are shifting to asset-light sectors and a small number of superstar firms that employ relatively few people. Some struggling firms have responded with cost-cutting measures such as squeezing suppliers or opting for automation, offshoring, or contract work. In real terms, wages remain below their 1983 levels in some large, asset-heavy sectors such as retail, transportation, and construction (Exhibit 3). The trends in these sectors alone mean that at least one-fifth of the US workforce has not advanced in more than three decades.

Workers now have fewer options when their pay stagnates. Rapidly falling costs of automation and the availability of lower-cost global labor have created more options for companies. As the nature of work has changed, the relationship between companies and workers has weakened. Temporary work arrangements and outsourcing are becoming more commonplace, and firms are better able to predict demand and schedule labor in smaller and more erratic increments. Workers now have decreased mobility, and the decline of unions has weakened their bargaining power. Large segments of the labor force lack the skills that the marketplace values.

Many of the trends we see today—including weak recoveries from recessions, a reweighting of the economy toward service sectors, and foreign competition—will persist into the future. Some appear to be accelerating, such as digital technologies reducing the need for low- and middle-skill workers. In the United States, some of the large and labor-intensive sectors that have already come under wage pressure (food service, manufacturing, and retail) appear to be most susceptible to automation in the future. The convergence of deepening income inequality and accelerating technological change increases the urgency to act.

Where do we go from here?

Disrupting current patterns in the labor market will require bolder interventions than what has worked in the past—and inaction itself would be a choice to accept the status quo of a two-tiered economy.

No single solution will be a silver bullet that will solve the problems of stagnant wage growth and growing disparities across the economy. These complex issues raise bigger questions than the usual economic debate, starting with how to address the deteriorating quality of jobs and where the approximately 45 million workers without post-secondary education fit into the economy. Some of the areas to explore include how to apply technology to improve the labor market for workers and whether incentives could boost private-sector investment in human capital. It’s also important to consider what kind of safety net will be needed in the future. If automation causes large-scale dislocation, we may have to debate measures such as a universal basic income or other types of redistribution.

Shifting the economy into higher gear is a critical first step. The United States has to jumpstart growth and move forward on long-recognized priorities such as restoring business dynamism, investing in infrastructure, improving productivity, and revamping education and training. And the nation will have to do a better job of executing on these goals.

More businesses need to start up, and more of them need to become fast-growing firms that create jobs. To accelerate productivity growth, more companies need to be encouraged to adopt the technologies and best practices of frontier firms. Small enterprises need assistance to seek out global market opportunities and foreign capital. US companies and investors need to recognize the long-term value of creating training pathways and better-quality jobs—not just out of social responsibility but to protect their own long-term interests.

But economic growth alone may not be enough. Growth also has to be more inclusive. We see four priority areas: reinvesting, retraining, removing barriers, and re-imagining work.

- Communities in distress need targeted investment from public, private, and foreign sources to bounce back.

- Continuous technological change means that mid-career workers need systems of lifelong learning to adapt—and currently the United States spends far less than other countries on helping displaced workers transition into new roles.

- It is possible to remove some of the barriers that keep workers from seeking out better opportunities, such as non-compete agreements, excessive occupational licensing requirements, inadequate child care and family support, and affordable housing shortages in booming job markets.

- This is a moment to reimagine work with more flexible models, a more sustainable version of the gig economy, and more creative options for older workers.

The United States can do better, and there are many levers it has yet to pull. Workers are not just a pool of labor; they are citizens and potential consumers. Raising wages would juice a latent source of demand—and doing so could set off a virtuous cycle of growth. Lifting up the millions who have been left behind can elevate the broader economy in the process.

The full research preview on which this article is based is available for PDF download, CLICK HERE to download.

About the author(s)

James Manyika is a director of the McKinsey Global Institute, where Sree Ramaswamy is a partner. Gary Pinkus is a senior partner based in McKinsey’s San Francisco office. Katy George is a senior partner in the New Jersey office, where Andrea Serafino is a consultant; and John Warner is a senior partner in the Cleveland office.